Early one Sunday morning in mid-August I woke up and checked my phone, and saw an eBay listing linked to a post on a Racine History Facebook group. The admin of the group was suggesting someone should buy these plates…and 39 minutes after he posted that plea, I checked the auction and it had ended. Someone had clicked the “Buy it Now” and the negatives were gone. It was the beginning of what’s going to be one of the biggest projects I’ve ever tackled.

This work totally diverges from our normal genealogy and family history research, and it’s a first for this blog to be writing about something outside of the journey of building out our son’s family tree…but something about doing this felt urgent. And luckily my wife indulges me when I tilt at windmills.

Tracking down the collection

After seeing the auction closed, I immediately emailed the seller with a polite request to confirm that the item had actually sold, and if there were any other cases that might be available. He replied back later that day that he had sold that case, but he was cleaning out a space for someone and there may be other cases. About a week later he reached out and said that he’d found 4 more cases, and agreed to sell them directly. We met him at a storage locker and I found he had 3 cases of 5″x7″ glass negatives and 1 case of 8″x10″ negatives. The larger plates were in very bad shape, but the 5×7’s were looked largely OK.

The seller was a bit taken aback at the level of interest he’d received on the auction, and wondered why they were so popular. I explained that a collection of this size of these plate negatives was very rare, and that it likely captured an amazing slice of life in Racine…a slice that would be lost if the collection were broken up. We talked about my intention to get the collection together, make sure the plates were archived properly, scanned and shared publicly, and then donated to a museum that could protect them. The seller agreed to forward my contact information to the person who bought the case of slide we saw on eBay.

About two weeks later that original purchaser reached out to me and I learned he had actually purchased 2 cases, and that he’d sell those cases to me…at a small profit. A few days later we picked up those cases, and we found the scope of what we had: 5 cases of 5″x7″ dry plate negatives, most with two images per slide, for a total of about 2000 slides and 3000-3500 images, as well as 1 crate of 8″x10″ negatives, about 200 total images.

Where did these images come from?

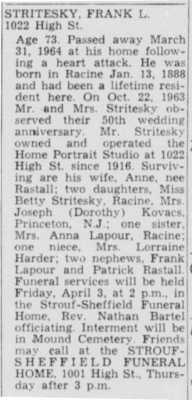

These images were taken by Frank Stritesky who operated the Home Portrait Studio at 1022 High Street in Racine from 1916 through his death in 1964. Frank and his wife Anne were of Bohemian ancestry, and they lived in one of the largest Bohemian neighborhoods in the US, so this collection is likely a great snapshot of that population as well as hopefully showing how the neighborhood changed over the nearly 50 years the studio was in operation.

These images were taken by Frank Stritesky who operated the Home Portrait Studio at 1022 High Street in Racine from 1916 through his death in 1964. Frank and his wife Anne were of Bohemian ancestry, and they lived in one of the largest Bohemian neighborhoods in the US, so this collection is likely a great snapshot of that population as well as hopefully showing how the neighborhood changed over the nearly 50 years the studio was in operation.

Frank was survived by two daughters, Betty and Dorothy. Betty never married, and lived with Anne until her death in 1973. Betty continued to live in the house on High Street until her death last year, and it looks like her friend that serves as the administrator of her estate is clearing out the house. The person that originally sold me the plates is a collector, and likely came across this collection as he helped clean out the home or through an Estate Sale. The negatives were probably stored in the basement of the studio, or the garage, which explains the condition issues.

As a side note, after a few posts that I made to the Racine History Facebook group another local historian reached out to me indicating that he had bought a case of plates from the family, before there were condition issues, as well as many prints made from these slides. He felt there could have been around 12,000 images total at the time of Frank’s death, which would mean our collection is only about 25% of what once was.

How are we archiving the negatives?

Our first worry is to get these dry plates stable, and protected, so they don’t continue to deteriorate. We have worked with large, important collections as a part of our family history research (Coming up with a plan to manage my new, huge family history collection) so we had a good idea of how to research the best way to archive these plates. We settled on Hollinger’s Four Flap Negative Enclosures (Four-Flap Document/Pamphlet Envelopes) placed in Dark Gray “Shoe Box” metal edge boxes (Short Lid Negative & Print Storage Boxes), surrounded inside with Ethafoam archival foam to cushion the slides (Artcare Archival Foam White Board). We can fit 70 slides in each box, and given how heavy they are, that works out to about 15 lbs. per box…which is manageable and easy to carry/store. Each box will be stored in a climate/humidity controlled room we have for our collections.

To clean or not to clean

Once I started unboxing the first crate of negatives, it became apparent just how affected by the environment these negatives were. The 5″x7″ were worse than I’d thought, and even the best of them shows a gradation in the photo emulsion that indicates likely water damage. Additionally most have a brown “dirt” on them that often caused the slides to stick together.

I have an extensive background in photography, having processed nearly 20,000 rolls over my lifetime. While my work is entirely on modern, plastic-based negatives, it still gave me confidence that I’d be able to master any needed cleaning techniques. My hope was that I could clean each plate, returning to as close as its original condition as possible. I was able to find an official Kodak publication that details the cleaning process for these exactly types of Kodak dry plate negatives, and it turns out I have most of the chemicals on hand since I still process my own B&W film from time-to-time.

I also reached out to several area museums and archivists in the area, and found white papers from archivists on how they had cleaned dry plate negatives like ours. The Kodak book was specific to removing what’s called “silvering” which is when the silver in the emulsion essentially tarnishes, which isn’t a huge issue with these negatives. It’s present in these negatives, but it’s not impacting. So then we decided to focus on the MUCH easier process of gently cleaning the dirt off the emulsion side of the slides, rinsing them in water, and drying them. The process is detailed by a former City of Toronto archivist (Cleaning Glass Negatives by R. Scott James) and we started with the most damaged example we could find, a slide that was barely viewable it was so dirty.

When we cleaned this first negative, we learned the truth: the “dirt” was not dirt, it was  what’s left over when the emulsion is damaged. It’s likely what’s left over when water gets between the slides and drys in that state, and what’s left behind after it’s cleaned is just clear glass. The emulsion is totally ruined in those spots, and so cleaning it doesn’t really damage the negative further, it just reveals the damage. Given the risk to many of these plates, and the risk of even washing the emulsion, I decided to avoid cleaning the emulsion altogether.

what’s left over when the emulsion is damaged. It’s likely what’s left over when water gets between the slides and drys in that state, and what’s left behind after it’s cleaned is just clear glass. The emulsion is totally ruined in those spots, and so cleaning it doesn’t really damage the negative further, it just reveals the damage. Given the risk to many of these plates, and the risk of even washing the emulsion, I decided to avoid cleaning the emulsion altogether.

I did decide to wash the glass side of each plate…until I started to clean with the first 5 slides. There was no damage, but there was no impact either. They didn’t look better, and it took a lot of effort to get them completely clean, without streaks. Since even just cleaning the glass carries a risk of breakage, and there’s no real value in cleaning them, we decided to not clean them at all short of brushing them with proper brushes…carefully avoiding any lose parts of the emulsion. Besides, there’s an adage among collectors of old valuables: they can be in original condition once…once you clean them, they can’t be uncleaned.

Scanning them for use

We reviewed the process UWM followed to digitize their 20,000 slide Polonia Collection (Digitizing Milwaukee’s Polonia at UWM Libraries), and it really is the way to best do something like this. However, we’re already spending about $500/crate in archiving supplies, and we don’t feel like spending the money on a Nikon D800 digital camera, so we chose instead of use the flatbed scanner we already own. It’s much slower per image, but we own needed hardware.

We own an Epson V550 flatbed scanner specifically to scan photos and negatives, and while it has great image quality, the negative scan area can only do 1/2 of the image per scan. We’ve created a custom jig to hold each plate as its scanned, and to ensure we capture the right area with each scan.

For the scans themselves we’ve largely adopted the Library of Congress standards for their Civil War Glass Negative collection (Digitizing the Collection). The first two scans are 1200 dpi at 16-bit grayscale, and I combine them in Photoshop and export them at the “Highest Resolution TIFF Images” standard in the LoC document. From there, I import them to Adobe Lightroom and put a loose crop on them (showing essentially the entire plate), straighten them if needed, and with no other digital alterations export them to the LoC’s “Compressed Service Images” standard (1024 pixel on the long edge, 8-bit grayscale, .jpg files). I then attach a proper citation to each image, and upload the images to our Archive site. These images are lo-res enough to take up very little space in our Archive, but sharp enough to see most of the detail in each slide.

The first box of negatives revealed

The first box of the first crate appears to come from 1917-1919. There’s a man in a uniform that was only in-use from late 1917 through mid-1918, and in another a woman is holding a magazine published in October 1919. There is a wedding party in one series of photos, and a good mix of children, family portraits, and individual portraits. Women were often wearing what I would have thought of as Victorian boots, and while smiling would have been very acceptable by this time, many of the adults have more of a scowl than a grin. Especially the men in the family portraits! There are quite a few men in uniform, right around the time of WWI.

The first box of the first crate appears to come from 1917-1919. There’s a man in a uniform that was only in-use from late 1917 through mid-1918, and in another a woman is holding a magazine published in October 1919. There is a wedding party in one series of photos, and a good mix of children, family portraits, and individual portraits. Women were often wearing what I would have thought of as Victorian boots, and while smiling would have been very acceptable by this time, many of the adults have more of a scowl than a grin. Especially the men in the family portraits! There are quite a few men in uniform, right around the time of WWI.

We’ve also learned that each crate is going to require 5-6 of the shoe boxes to hold all of the slides, and that the crates weigh about 90 lbs. each!

What’s next?

A LOT of work! This box took about 2 straight days to scan, and another 2-3 days to combine the photos and prepare them for presentation. It then took a day to give them the proper index data in the Archives, so each box represents about a week’s worth of full-time work, so each crate will take about 6 weeks total to process. We are going to avoid giving updates for a bit after this, so we can focus on the scanning/archiving piece of this project…with an eye of getting these negatives processed and safe as quickly as possible.

We are also going to keep looking for any additional crates, to see if we can add to what we have, and we’re going to keep trying to get a copy of the key that links the # on each plate to the person in the photo. In the meantime, if you recognize anyone in these photos please let me know and I’ll update the information.

Finally, it’s time to start discussions with local History Societies and Museums to see who might be able to house this collection permanently. Something like this, something this historic and special, can’t ever be properly safe in my home. It’s also expensive for institutions to house these items, as well as getting them into an archival state…I’m hoping that by doing most of the work for them, and doing it properly, places will be interested enough to take in this collection when the time comes. Starting that conversation early on should help that effort.

Where are the pictures??

Click this link to view the Archives, and to browse the first 70 images from this collection: Home Portrait Studio (Racine, Wisconsin) Collection

Please share, discuss, and help identify the surviving families who might never has seen these images. But most of all, enjoy this special slice of Racine’s history!!

2 thoughts on “Our project to save a piece of Racine, Wisconsin history, Part 1 – Getting Started”